Forests After the Fire: Salvage, Restoration & Regeneration

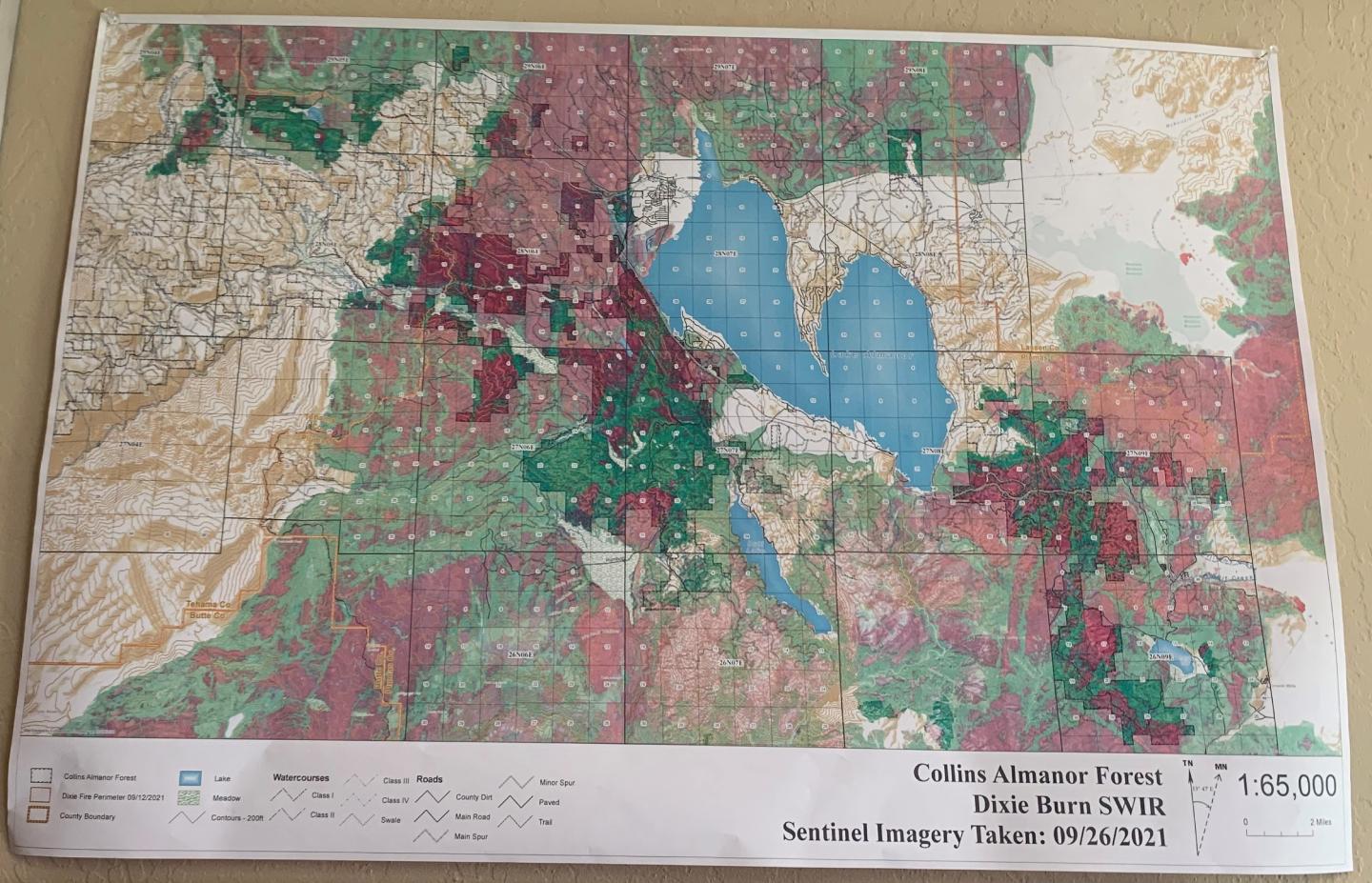

After the devastating Dixie Fire of 2021, our VP of Sustainable Impact, Terry Campbell, toured the Collins Almanor Forest to survey the extensive damage there and talk to forest managers about the path forward.

On July 13th, 2021, a tree fell onto a Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) distribution line near the Cresta Dam in California igniting the tree at the base. That’s all it took in drought-stricken California to start a wildfire that grew to 960,000 acres, covering five counties, destroying at least $1 billion of forestland, decimating the town of Greenville, CA and coming very close to burning the town of Chester and the Collins Pine Co mill located there. That wildfire was called the Dixie Fire.

The town of Chester, California is 50 miles north of the Cresta Dam, and has been the home of the Collins Pine sawmill since 1943. The Collins Almanor Forest and mill are the first in the US to become certified by the Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC ®) The property was purchased by the Collins family in 1902 and has never seen a clearcut. It is 10 miles from Lassen National Park, includes a segment of the Pacific Crest Trail, and is a truly magical place. It has been the vanguard for an ecological forest management regime for 80 years. In my 23 years of selling sustainable wood products, I can say with confidence that I am most proud when I get to connect our customers with products from Collins.

It was this respect for Collins that drove me to reach out to them in the spring of 2022 with a request to pay them a visit and see how things were coming along in the months following the Dixie Fire’s destruction. I was introduced to their Chief Forester, Niel Fischer, who offered to squeeze me into his schedule on May 20.

Driving down from Portland, Oregon, I crossed over the north portion of the fire damaged earth near Old Station, California on CA Highway 44. Aside from noticing the random nature of which a fire burns, I also lost count after noting more than 50 log trucks heading north to sawmills with charred logs in their beds. After a fire event the forest landowner only has 2 years to turn the scorched trees into lumber before the wood starts to decay and insects slowly start to break it down. With almost a million acres burned in the Dixie Fire, it was no wonder there was a bit of a salvage logging bonanza.

As I crested a hill on the northeast edge of Lake Almanor on a blue-sky day, I could see the intense fire damage across the lake and the closeness with which that fire came to the mill complex and the town of Chester. I met Niel at the main office, and we quickly jumped into a truck and headed out to look at the remains of the forest.

Niel told me that in this part of the world two things dictate how a forest fire moves: wind and slope. High winds mean bad things and being uphill from a fire can put you in danger. On August 2, the fire was southwest of Chester and in a lull where it had settled down. Suddenly, the wind picked up speed and sent the fire roaring across 106,000 acres in six hours. It was this day, August 3rd, when the fire blew along the fence line of the mill and the Chester airport. It was only for the heroics of CAL Fire crews that the fire did not engulf and destroy the town and mill site.

As Niel described his firsthand experience in the line of the Dixie Fire, I could tell that the intensity of the three-month ordeal had a lasting impact. Fifty percent of the 95,000-acre Collins Almanor Forest was burned in the Dixie Fire. Now they are left to balance which logs they can salvage with what should be left to start the regeneration process. The Collins forest management philosophy has always been to allow nature to re-plant its trees and to nurture them along. However, the damage from the Dixie Fire is going to require replanting the acres lost by hand.

Going into the tour I had so many questions I wanted to ask about the future, but I learned that the on-the-ground priorities were the focus. One of the comments Niel made that stuck with me had to do with the forest management priorities of the various landowners, public and private, in the area and which forests exacerbated the Dixie Fire situation. Some forests in our region are overcrowded with more trees than the ecosystem can handle, and it was viewed in this part of the West that those forests may have made the fire more intense and last longer.

Members of the Collins Forestry team gathered historic records, dating back a hundred years. They found that forests in the early 20th century had lower density (less basal area), more pines which are more fire resilient than firs, and a larger average tree size than the forests of today. In a follow-up email Terry Collins painted a picture of the forest conditions and priorities we should be working towards. “If we want to manage our inland western forests to bring them back to a condition where they will be more fire resilient, then opening our forest stands in all age classes, harvesting the fir aggressively while leaving the pines longer in the stand, and maintaining a wide range of tree sizes is a good model.”

Climate scientists talk about ‘negative feedback loops’ as they relate to climate change. For instance, HVAC systems emit a lot of greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) that are warming the planet that will require more people to buy HVAC systems that emit more GHGs and so on. The negative feedback loop in this scenario is this: if we don’t find collaborative methods to thin our public forestland, then they will burn at an intensity that may leave the forest and soil too unhealthy to regenerate. As I learned on my visit, when this many trees burn, the regional sawmills can only handle so many charred logs in a day. As they scramble to salvage the fire damaged logs, they can’t even consider bringing in logs from thinning projects. Without a market for logs fewer thinning projects will take place and more fires are likely to be high intensity events.

Obviously, we would rather mill logs from thinning and restoration projects that are protecting ecosystems services and communities, but we can only do that if we find ways to stop the post fire salvage logging bonanza. The way to stop the bonanza is restore the forest to a more resilient state that allows low intensity fires as part of their natural ecosystems. The result of inaction is large and destructive wildfires, loss of life, destroyed ecosystems, major carbon release, etc.

The US Forest Service does have a system of Collaboratives in most National Forests of the West that establish the use of a multi-stakeholder decision making process to assess, plan and implement restoration projects on our public land. These Collaboratives are quite effective in the Colville (WA) and Malheur (OR) National Forests in which both forests share similar composition to the area the Dixie Fire burned.

Is it too late to roll-up our sleeves and engage with our community members in these Collaboratives to chart a new course for our public lands that strikes a balance between forest resiliency and ecosystem protection? I hope not.

Project Support

Find local sustainable wood products in Portland Oregon

Our Why

We exist to promote Good Wood in the Pacific Northwest and beyond

Sustainable Northwest Wood

2701 SE 14th Ave.

Portland, OR 97202

Monday - Friday

8am to 5pm

© 2025 Sustainable Northwest Wood

Our nonprofit parent company is Sustainable Northwest